The hand weaving industry in the Philippine Cordilleras today was popularized by Narda’s along with other enterprises. Along with the other weaving groups existing today, Narda’s maintain the back strap weaving for culturally specified purpose fabrics and the upright loom for commercial purposes.

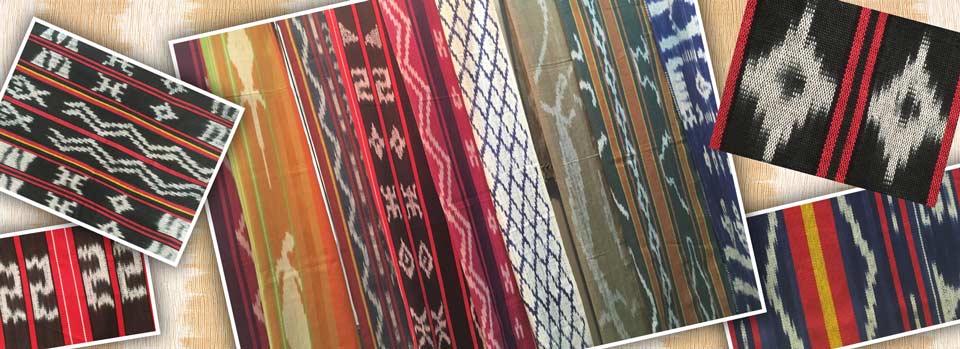

The upright loom is adopted by the Cordillerans, or more popularly known as Cordis, from the lowlander Ilocano loom. The Cordis, like Narda’s, see the use of the upright loom, which can accommodate wider warp span and longer weft, in commercial production of rolls of fabrics for dresses, scarfs, shawls, polos, barongs, hoodie jackets, bags, placemats, runners, wall hangings, etc. Narda’s even innovated on colors, using shades which are not in the traditional palette to adopt to current lifestyle.

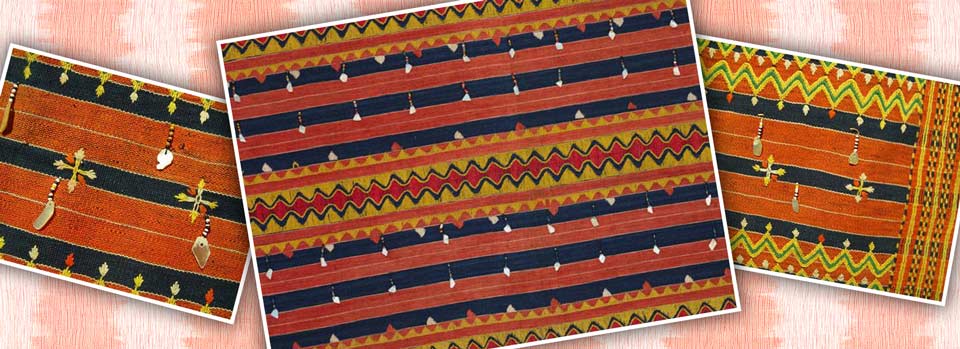

Culturally specified purpose fabrics woven in the backstrap loom includes the blanket for the dead, wedding garb, and other traditional fabrics used in the Cordis’ cultural rituals. The back strap loom parts are lasting and do not need difficulty in maintaining because these are made of wood, sticks, bamboos and rattan so they do not corrode to form rust.

Back strap weaving in the Philippine Cordilleras is a living tradition promoting Cordilleran values of cooperation, solidarity, teamwork, cohesiveness and creativity.

The hand weaving industry in the Philippine Cordilleras is not just a tradition but also a means of community teamwork, socialization and cooperation. Weavers are primarily farmers. Weaving is done after farm work is done. Weaving in the early times was not considered work but a form of recreation. In the process of winding, warping, weavers discuss issues, joke with one another, eat together and communing with each other becoming closer and stronger as a group through weaving cooperation. Backstrap weaving does not need a wide area and it’s mobile because the parts are not assembled upon actual weaving, just rolled, it can be moved from one place to another without difficulty. Since it is mobile, weavers can decide to assemble and weave anywhere, under their houses or a tree where others can just come and socialize with them. Any passerby can stop and help in the weaving, entangling any entangled thread or would do any errand for the tied weaver.